Freedom from Masters and the Next Indie Revolution

When we own what we build, then we own ourselves. When we build for others, we find meaning within.

October 24th, 2024: Hellooo! It’s way after when I was hoping for, but it’s been an incredibly busy time and this post took much longer to come together than I expected. After my last post in Greece, I went to India for two weeks, then San Francisco for July 4th and finally to Italy before finally settling back in NYC. Visiting old friends in San Francisco and making new friends in Italy just really made me thankful for the wide variety of people I’ve been able to meet in my life. I also moved places as my short term lease ended and I made the decision to move into a long term one with a friend. Given all the chaos during that time, I’m excited to report that, I finished fleshing out my feature film idea (through The Gotham Writers Workshop), as well as a TV Show Pilot (through Anatomy of A Script, recommended by a friend). It’s been more sleepless nights in the last few months than the last few years, but I’m settled in NYC now with no great travel plans on the horizon and I have been delighted beyond my expectations at how much I have loved the new projects I have taken on.

TL;DR - As I discover my new love of film and my growing love for writing, I consider how I can build as a full-time indie creator without a reliance on major institutions. Inspired by an underground world of massive indie creator successes, I uncover the strategies on how to pursue success this way. I also come to the revelation that we are currently witnessing an Indie Revolution that has the power to save us from The Problem of Ownership, which may be the defining problem of our generation.

Sitting in a coffee shop, sipping chai, it dawns on me that it’s been over a year since I started my sabbatical. Around this time last year, I would spend hours just walking around Japan, tantalized by the unknown possibilities. I remember one day I was so drawn to this book I came across that I ended up putting every page through Google Translate so that I could read it. It was called bloom where you are planted by Kazuko Watanabe and in it, it said, “When you realize that waiting can give you peace of mind, the “present” you are living in becomes more fulfilling”. I might not have realized it then, but this moment captured the essence of why this sabbatical was so special to me: it was about finding a deep peace in leisure, without putting any pressure on it to lead me somewhere or produce something.

My return to full-time work marked my transition from exploring what life feels like untethered to any work to an intentional experimentation with different kinds of work and the lifestyles made possible through this choice. Through this experimentation I have discovered film and it gives me great joy to reflect on the threads from the past this new passion brings together. It has the social element of managing the ideas and personalities of a deeply interdisciplinary team as in Product Management, the creative thirst for new ideas as in entrepreneurship, a depth akin to research papers in philosophy, psychology, etc. and a powerful medium for inner expression and emotional healing that comes with writing. With every new interest I explore, I better understand myself through the recognition of overlapping feelings in different fields of work.

What began from watching an innocent character analysis on YouTube has quickly become a side of myself I can no longer imagine being without. But having this new passion now leads me to the inevitable question of how do I express it? Should I pursue this full-time or on the side as an indie creator, a term meant to refer to individuals who produce their work independently, often without the backing or influence of large organizations? Is it possible to pursue it full-time without resigning myself to the structures and expectations of the institutions of the industry? These are existential questions many creatives face and, for the past few months, they have plagued me too.

Why is this post so important?

It will be said that while a little leisure is pleasant, men would not know how to fill their days if they had only four hours’ work out of the twenty-four. In so far as this is true in the modern world it is a condemnation of our civilization; It would not have been true at any earlier period. There was formerly a capacity for light-heartedness and play which has been to some extent inhibited by the cult of efficiency. The modern man thinks that everything ought to be done for the sake of something else, and never for its own sake.

I sit on a man’s back, choking him and making him carry me, and yet assure myself and others that I am sorry for him and wish to lighten his load by all means possible…except by getting off his back.

— Leo Tolstoy. Writings on Civil Disobedience and Nonviolence

What I have discovered is a new way of thinking about work. A new standard to strive for when it comes to how to work. This new standard involves building in periods of varying intensity according to the principles of Slow Productivity, without the pressure of external expectations and incentives, and focused on the intrinsic reward of helping others and doing work you’re proud of. It is the pursuit of building as an indie creator full-time. There is so much I discovered from going down this rabbit hole of how to succeed as an indie creator that I am going to break it down into two parts.

Part 1: In this part, I want to explain what it means to take an indie approach. I want to share the history of the ideas and breakthroughs that led to indie creators being able to go toe to toe with the behemoths of the time and reach stratospheric heights and how we can incorporate those lessons today into how we approach building.

Part 2: In this part, I want to explore the possibilities of the future. I want to share how fundamental ownership inequality has become a defining problem of our time, and how an indie revolution will give us all the tools we need to steer our future into the indie paradise it can be.

So, without further ado, let’s get started! Fair Warning: this isn’t going to fit in an email format.

Part 1: Freedom From Masters Through The Indie Approach

What is the Indie Approach?

I know of one gaming company in Los Angeles that had a stated goal of turning over 15 percent of its workforce every year. The reasoning behind such a policy was that productivity shoots up when you hire smart, hungry kids fresh out of school and work them to death. Did it work? Sure, maybe. To a point. But if you ask me, that kind of thinking is not just misguided, it is immoral. At Pixar, I have made it known that we must always have the flexibility to recognize and support the need for balance in all of our employees’ lives. While all of us believed in that principle—and had from the beginning—Toy Story 2 helped me see how those beliefs could get pushed aside in the face of immediate pressures.

Since the inception of the academy awards in 2001, Pixar, now owned by Disney, has won the Best Animated Feature Oscar 11 out of 24 times (Next Best Picture). However, behind this success is a dark grueling work ethic so common in the animation industry it has a name, crunch time. The creation of Toy Story 2 left a third of the animators suffering from repetitive stress injuries and carpal tunnel syndrome. One employee was so fatigued that he left his child in the back of a car in the Pixar parking lot (LA Times).

Is this just the cost of greatness? If I’m not willing to do this, does this mean I should just pursue writing and film as hobbies in my leisure time? If I do pursue this as an indie creator without the support of a major institution, does that put a ceiling on the level of success I can achieve? For me, deciding between these unacceptable trade-offs had left me lost. That is until I came across the story of a very special indie creator called Vivienne Medrano, often referred to as VivziePop.

Vivienne Medrano, or VivziePop on YouTube, is an animator who also had big dreams of creating her own show, same as many of the animators at Pixar. However, she approached creating her show, The Hazbin Hotel in a very different way.

Instead of working on the show in one intense period under crunch time, Vivienne worked on the show on and off since middle school, in college, and even after becoming a professional animator. Instead of pursuing support from major studios and the expectations they come with, she relied on a community of friends and contributors. When she did finally finished the pilot, Vivienne didn’t sell the show to a network and instead just posted the pilot for free on YouTube. That pilot went on to get over 100 million views, the most of any animated show on YouTube. Only after proving out its success and leveraging this success to have major creative control did Vivienne accept major funding from Amazon Studios and A24, where it again broke records, having the largest global debut of any new animated series on Amazon Prime!

VivziePop’s story is not just exceptional in its level of success, but more importantly in how she was able to succeed. It is emblematic of what I refer to as The Indie Approach. This approach essentially boils down to 3 things:

Work is pursued in accordance with the principles of Slow Productivity, with an obsession on quality and working at a humane pace with the long term in mind.

There is ownership over the work. Creators have choice over what they work on and own the wins and the losses resulting from their choices.

Work is done for its intrinsic benefits to the creator or a community the creator cares about, not under the pressure of reaping extrinsic rewards or satisfying a 3rd party whose interests are not aligned with the creator or community.

Through the indie approach, we can learn to build in a way that is kinder to ourselves, allows us to fully unleash our creative potential, and involves those we want to help in bringing about positive change for themselves.

The History of Indie

When I set off down this rabbit hole, I discovered something really fascinating: that these indie successes are not just independent examples that occur here and there, but that in fact there is a pattern to these successes. There have, in fact, been waves of indie successes that were set in motion by technological and ideological revolutions.

So, before diving headfirst into how to be an indie superstar like Vivienne, it can be helpful to understand the history of indie creators, what were these waves of indie revolution, and what are the conditions that helped spur them on. The term indie, short for independent, was popularized during the first indie revolution, The Indie Music Revolution of the ‘70s, and referred to an approach to building something without a dependency on major traditional institutions, usually replaced with a dependency on the community it was created to serve.

The indie movement of the ‘70s occurred in response to the consolidation of the music industry, and was spurred on by the counterculture movement of the 60s and technological advancements such as the more cost-efficient cassette tape and cheaper home recording equipment. This gave indie bands with a scrappy attitude a chance to compete against the behemoth record labels of the time.

The Grateful Dead, for example, was able to bypass financial reliance on a major studio for mass-producing tapes by allowing fans to buy their own tapes, record their live concerts, and then distribute these tapes to friends. Similarly, the band Marillion was able to bypass relying on a major studio to pay for recording their album, Anoraknophobia, through bootstrapping the production from pre-orders from fans. The reason that this revolution was so important was because it showed that independent musicians could be scrappy, take risks, and create new genre defining music, not in spite of, but because of a lack of reliance on major institutions.

Soon after this first revolution, we saw the second indie revolution, The Open Source Revolution of the ‘90s, which was spurred on by the explosion of the internet and the World Wide Web. It was made possible by key technological advancements including version control, improved access and bandwidth of high speed internet, as well as real time collaboration tools and resulted in the ability for creators to coordinate large scale efforts without the assistance of any central authority. Email, Wikipedia, Linux, and most of the web was built by indie creators in this way. While the movement of the 70s showed creators they could lean on their community for support, the movement of the 90s was a complete paradigm shift in making your community a co-creator. It showed that creators could profit and build healthy competitive advantages through a policy of transparency, openness, and collaboration instead of gatekeeping and consolidation. From this movement came Linus's law, or the assertion that "given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow".

The legacy of these indie revolutions manifests strongly in the success story of indie creators today, in a way we rarely hear about. Ghostlight, an indie film claimed by some critics to be the movie of the year, was created leveraging the scrappy ethos of indie bands of the 70s movement. Tim and Carrie League similarly embodied this ethos when they lived in the theater they leased, drove back and forth to LA to pick up film rolls, and learned how to operate a pizza oven to get food and theater combo chain The Alamo Drafthouse Theater off the ground without major funding.

According to Professor Dileep Rao, 9 out of 10 of America’s billion-dollar entrepreneurs took off without early-stage VC. Andreessen Horowitz, in this blog post, argues that the open source revolution is just getting started: citing that companies that open sourced their technology raised over $10B in capital, with three-quarters of the companies and 80% of the capital raised to have come about after 2005. These revolutions may have started in the past, but they are on-going today and, if we learn the lessons their stories teach us, we too can build with the freedom rock stars had in the ‘70s and the purpose developers of the ‘90s had when building the internet.

How to Build Indie

When we own what we build, then we own ourselves. When we truly build for others, then we can truly get joy and meaning from our work. So what lessons have I learned from studying the stories of indie creators? I’ve learned that while there are a lot of different ways to succeed, there are patterns in indie success stories that can be helpful to learn from. Here are just a few that I observed:

Let your community help you: When Pixar was creating Coco, it did so in near total secrecy. VivziePop, on the other hand, openly shared the art style and concept of her show years before completing it. She even encouraged and shared fan art from the community, making community members feel part of the show’s story and success. It may seem counter-intuitive, but getting the people you are trying to help to help you makes the community feel part of your success and kick off a reciprocity loop that leverages The Ben Franklin Effect. When Nick Greene and the founders of Thrive Market got rejected from every major venture capitalist, they ended up fundraising through collecting hundreds of small checks from bloggers in the lower access communities they were trying to serve. This ownership incentivized consumers to spread the platform within their communities. Paul Bohm took a similar approach to marketing his on-chain ridesharing app Teleport, incentivizing word of mouth through giving drivers ownership in the company as opposed to spending money on external channels.

Stagger Financial Investment: Creative pursuits like making a TV show or writing a book often require significant time and money upfront, with high risk. In her TED Talk, Elle Griffin suggests a radical approach: releasing books one chapter at a time, similarly to TV shows, allowing creators to stagger investment, gather feedback, and adjust course early. This strategy can benefit indie creators who lack major funding. For instance, A24 only invested heavily in films that performed well in early screenings, and Pixar monetized incremental progress by selling software like RenderMan and doing commercials. While it’s not always an option, finding ways to stagger costs, monetize progress, or minimize upfront investment can make all the difference for indie creators.

Catch a Wave: It's often easier to succeed as an early player in a small, growing market than in a large, crowded one. Hazbin Hotel didn’t aim for mass appeal, and instead targeting niche communities—BDSM, religious themes, LGBTQ+ representation—whose voices were growing but lacked content that catered to them. YouTuber schnee grew his channel by quickly creating content for emerging shows, riding the wave of early search traffic. In Nothing Ventured, Everything Gained, Professor Dileep Rao similarly highlights how companies like Intel, Apple, Genentech, and Cisco capitalized on emerging markets during tech revolutions. Indie creators can outmaneuver giants by targeting future growth areas, even if the current payoff seems small. I’m hopeful that building in AI Governance before regulations take hold is an example. Though easier said than done, catching a wave in an emerging market can set indie creators up for success.

Harness The Beacon Effect: VivziePop exemplified the "Beacon Effect" by focusing on quality over quantity, dedicating years to producing a studio-level pilot for Hazbin Hotel without professional backing. This one standout project showcased her potential and helped secure a deal with Amazon, despite her lack of experience. The Beacon Effect involves pouring resources into a single, high-quality project that acts as a proof of concept, attracting attention and future opportunities. A friend of mine in film school is using this strategy by pooling resources with other students to create one big film, instead of making smaller, individual ones. A24 also followed this path, focusing on a few high-stakes projects like Moonlight, Hereditary, and Everything Everywhere All at Once, instead of spreading themselves thin across smaller-budget films.

The indie approach is about a fundamental shift in priorities when building. Instead of speed, scale, and external validation, it’s about prioritizing ownership, quality, and joy in your work. While it’s taken some practice, I have, in my own life, begun to take a step back and ask myself: what would be the indie way to approach this?

In my AI Governance work for example, I’ve considered that instead of raising money to hire expensive AI talent, what if there was an open source way to collaborate on building solutions to client problems in a way that appropriately compensates contributors? A start-up called Molmo successfully leveraged a similar strategy with their completely free and open source AI Model. What if, instead of my friends and I each working alone to publish the best content we can write, several friends and I pooled ideas and time to write much better content, leveraging The Beacon Effect to create something better than we any of us could create alone. This was a strategy successfully used by the community of ghost writers that created The Hardy Boys. What if, when making indie films, I encouraged and shared fan art as VivziePop did, or even could allow fans to fork the film and see what it looks like with a new ending?

The indie approach is a mindset that, if honed well, can completely change the way you look at building out ideas. It can help you see new paths towards building in a way that keeps the joy and creative freedom at the forefront of the journey, even if it means delaying instant gratification and external rewards and making a difference one person at a time.

Part 2: Addressing Fundamental Inequalities through The Ownership Revolution

There is no denying that today’s elite may be among the more socially concerned elites in history. But it is also, by the cold logic of numbers, among the more predatory in history. By refusing to risk its way of life, by rejecting the idea that the powerful might have to sacrifice for the common good, it clings to a set of social arrangements that allow it to monopolize progress and then give symbolic scraps to the forsaken—many of whom wouldn’t need the scraps if the society were working right.

In 1998, a landmark antitrust trial put Microsoft in the hot seat for integrating its Internet Explorer browser with its dominant Windows operating system. Microsoft’s legal defense team argued that while it did indeed have a large share of the market, where was the consumer harm? At face value, this argument may seem to hold up for a lot of the consolidation we have seen in the tech industry and beyond. While an oligarchy with unprecedented control over the internet, these masters seem socially conscious and responsive to customer grievances. Furthermore, much of the value companies like Microsoft, Uber, Facebook, and others provide comes from leveraging the network effect, where the value of these platforms to us is in that everyone uses them. So, where then, is the harm?

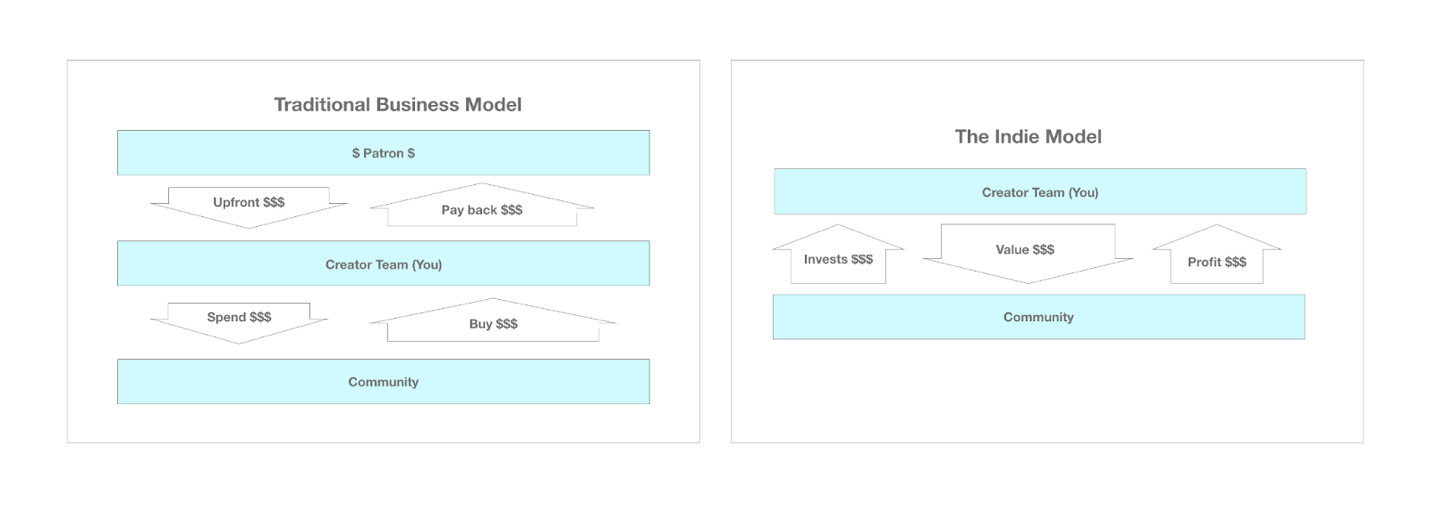

The Indie Revolution of the ‘70s taught indie creators how to depend on their community as opposed to their label. The Indie Revolution of the ‘90s taught indie creators how to coordinate efforts on a massive scale without a central authority. In his book Read Write Own: Building the Next Era of the Internet, Chris Dixon argues that there is massive harm in this consolidation and the movements of the past don’t go far enough in terms of their revolution. There is one more revolution left, and that is The Ownership Revolution. Through the Ownership Revolution, indie creators not only leverage the community for help, but effectively distribute ownership to this community, allowing them to benefit along with the creators.

Dixon highlights that while these corporations played nice at first, when they were in their attract phase, they are now in their extract phase, stifling innovation and creativity, charging exorbitant take rates, and capturing an unfair share of the rewards from the efforts of creators. This is because we, who enrich and build upon these platforms, have no ownership in these platforms and no means of leveraging our ownership to effectively bargain against these platforms. In this part of the post, I want to detail how The Ownership Revolution can specifically address 3 fundamental variants of The Problem of Ownership:

The Problem of Structural Ownership Inequality & Expanding the Pie: Ownership is the only true vehicle for wealth generation and so, to address true in-equality necessitates new models of ownership re-distribution. A great feature of ownership is that owners can transfer ownership to others creating a virtuous cycle that expands the pie for everyone.

The Problem of Network Effects & Lock-In: Network effects offer massive benefits through scaling their value with their size and leveraging economies of scale, but result in lock-in which leads to consolidation and anti-competitive practices. Interoperability and the ability to fork and modify existing creations can help network effects flourish without lock-in.

The Problem of Mass Scale Collective Bargaining: As massive corporations and AI seek to consolidate information and content, individual contributors don’t hold enough bargaining power individually to fairly represent their interests. The Ownership Era brings with it a guiding philosophy of mass collective bargaining which could lead to a more sustainable split of profits for everyone.

While building indie offers one a path to building in an intrinsically fulfilling way, it may more importantly sets the stage to rewrite the rules of how ownership is redistributed, leading to a more fair and interesting world for all of us.

The Problem of Ownership

In business, permission becomes a pretense for tyranny. Dominant tech businesses leverage the power of permission to thwart competition, desolate markets, and extract rents. And those rents are exorbitant.

– Dixon, Chris. Read Write Own

As children of immigrants, we are often taught that hard work is the key to financial success. However, this is only part of the story. The real key to wealth generation is ownership. As Nathan Schneider says in his book Everything for Everyone: “One way or another, wealth is going to the owners—of where we live, where we work, and what we consume.” This is why today, we are not just facing a problem of income equality, but more fundamentally Ownership Inequality.

Housing is a great example to help understand the critical difference between these problems. If we are able to successfully redistribute wealth, then more people will be able to afford homes in the short run. But, if ownership is never transferred from the wealthy, then the money will simply just flow back to the wealthy (Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland). On the other hand, if people are able to own the homes they buy, then they can generate wealth from the home when the value appreciates. This is exactly the policy that the U.S. took in the 1950s with the G.I. Bill when it enabled families to obtain mortgages with low down payments and affordable terms and it led to massive wealth creation for the middle class.

An additional second order benefit of ownership distribution is that when people own things then they can also transfer that ownership to others, allowing for more creative uses for our possessions. For example, if you own your house, then you can put solar panels on the roof and make money selling energy back to the grid, or you can sublet a room and put it on Airbnb. In fact, the $200 billion sharing economy is built off of this premise: if you own your car, you can become an Uber driver. If you own your car’s data, you can earn from sharing it on the on-chain platform DIMO. Through an indie approach, ownership goes to creators and community members giving them a shot to generate wealth. If only the wealthy can afford to take the risks of ownership, then only the wealthy will be able to become wealthier. Implementing levers of ownership redistribution will not only be the only real way to address this in-equality, but also help expand the pie for everyone.

Unleashing The Network Effect without Lock-In

As corporate networks gained ground, their optimal business strategy switched from attract to extract. With so many corporate networks switching to extract mode at once, power rapidly concentrated. APIs withered, interoperability fizzled, and the open internet got packed away into silos.

– Dixon, Chris. Read Write Own

In the early 2010s, after years of letting 3rd party apps such as Zynga, Vine, and Tweet Deck grow through their platform, Facebook and Twitter suddenly cut off support for these 3rd party applications. In 2021, Facebook blocked Thea-Mai Baumann from her own instagram account @metaverse when it decided to change its name. When faced with antitrust competitive lawsuits years later for such behavior, Facebook responded by saying “This restriction is standard in the industry”, citing similar policies at LinkedIn, Pinterest, and Uber, among others.

The reason these companies get away with such practices today is also a variant of The Problem of Ownership. We don’t own our own names or accounts on these platforms and so effectively have no say about what the platform chooses to do with them. However, The Ownership Era of the indie revolution paints a radically different picture of the possibility of the future through the advent of two key philosophies: interoperability and forking. With new social media networks built on-chain users would have ownership over their account and network and be able to seamlessly take it with them across platforms.

However, this philosophy doesn’t require blockchain. As a writer on Substack, I have the email addresses of all my subscribers and therefore can export my reader list outside of Substack. Similarly, I’ve noticed these days it’s more common to exchange phone numbers with people as opposed to social media accounts as these phone numbers can act as interoperable identifiers that new social media platforms use to import your network automatically. The future of creating indie is not just about embracing technological innovation, but demanding interoperability as a core feature of the platforms we choose to support.

Now it makes sense why we, as users, would want Facebook to allow us to take our user base across platforms, but why would any company pursuing the interest of its own profits ever make such a decision? Well the most successful website building platform on the internet, Wordpress, can provide a great example of how to leverage The Ownership Era’s principles for profit. Wordpress is an open source website builder which itself was created from forking, or copying over, another open source blogging software called b2/cafelog. Since its creation, 3rd party plug-ins and apps such as WooCommerce, Astra, Elementor, etc. have flourished under Wordpress’s open source philosophy and Wordpress claims that an unbelievable 43% of all websites on the internet are powered by the platform. While leveraging the open source core code is free, the Wordpress economy makes a hefty profit through charging for hosting services, premium themes and plugins, and a freemium model and is estimated to be valued at over half a trillion dollars.

It can be incredibly rewarding to create value not in spite of, but because of indie values. Network effects are why electricity is as affordable as it is, why information is as easily accessible as it is, why most of the major software platforms are as valuable as they are, but further consolidation and lock-in is a consequence we must no longer tolerate. Building with inoperability and forking in mind will allow for incredible new innovations to be built on top of what already exists.

Large Scale Collective Bargaining

Blockchain networks could be the foundation for a new covenant. Among other things, blockchains are collective bargaining machines. They are perfectly suited to solve large-scale economic coordination problems, especially when one side of the network has more power than the other side.

– Dixon, Chris. Read Write Own

In the 1980s, the automotive industry in the U.S. began adopting robotic technology in their assembly lines, which, despite the best efforts of auto workers, led to great job insecurity and displacement. In 2023, the Writer’s Strike led to securing a contract with Hollywood that set a historic precedent that writers could decide how they wanted to use generative AI and would get full credit and compensation for work, even if it was AI assisted (Brookings). While there were many key factors to why each movement went the way that it did, two of these factors were definitely a technological understanding underpinning the movement and the scale of cooperation the WGA (Writer’s Guild of America) was able to reach in order to have collective bargaining power with the industry.

As Dixon explains, content providers today are too scattered to have any power against the behemoths that control distribution such as Google, Facebook, etc. What if, earlier on, all content providers, just as the writers in the 2023 strike, had also taken collective action to ask for more transparency, more say, and a higher take of profits? Then these content providers, many of whom are indie creators, could have a greater share in the massive industry that they are helping to create. Due to the Ownership Revolution innovations such as blockchains, DAOs, smart contracts, among others can help codify and scale the coordination needed for large swathes of small owners to represent their interests.

Specifically there were two areas where this could be applied in the future that Dixon mentions in his book that really excited me. The first was AI generated images, where a blockchain would enforce an attribution system and accordingly allocate revenue from the image back to the artists who contributed to the training of the AI system. The second was in identifying deep fakes, where creators could sign their name on their creations and 3rd parties could attest to that ownership and it’s all recorded on-chain, creating an immutable audit trail that could easily be checked by anyone.

As we head towards the future of AI and many other industries, we should maintain the importance of building in the indie way with a proactive distribution of ownership, attribution, and reward as well as the ability for collective bargaining, just as the WGA did for its writers. Otherwise, we risk the further consolidation of power into private interests, leaving us as robotic automation left auto workers, displaced with an uncertain future.

When we focus on redistributing ownership as opposed to just wealth, we give homeowners the keys to their own social mobility. When we grow network effects with inter-operability and forking in mind, then we can become the shoulders others stand on to express their creativity. When creators pool what would individually would be far too little ownership to make a difference, then we create an effective balance of power that allows us all to grow in a healthy way.

From the stories of indie creators we’ve explored so far, it can becomes clear that indie success is not defined by it’s absence of reliance on major institutions, but the presence of it’s ability to build in ways that inspire trust in a community to join in and help out, so everyone can win.

What can this mean for us as a society?

The indie approach is not only a set of principles to be leveraged by indie creators, but a community driven philosophy that can more broadly be leveraged to rethink our most fundamental institutions. For example, new regulations in the United States such as the National Worker Cooperative Development and Support Act are encouraging organizations to be set up as worker cooperatives where organizations can more easily be owned and managed by workers.

Mondragon is a group of 92 such organizations, all of which collectively are 80% owned by its workers. Major decisions are discussed and voted on in a General Assembly and supervisors are elected by worker representatives. Many workers are not only owners, but also customers as Mondragon expands into creating the universities, houses, and preschools that were lacking in the communities where workers lived. While many corporations today reserve most of the ownership for leadership and external investors, Mondragon’s approach puts workers directly in the driver's seat of addressing their own needs as well as incentivizes them to address the needs of the company (the company does belong to them after all). While taking care of workers, Mondragon has also been an exceptionally successful organization, growing to over 70,500 workers and €11 billion in revenue last year.

Red Hat, acquired for over $30 billion, is another organization that embodies the indie mindset by providing open-source software like Red Hat Enterprise Linux (RHEL) for free. The way Red Hat makes money is through subscriptions for updates, security, and support, as well as consulting and training services for businesses. However, as Jim Whitehurst, the C.E.O of Red Hat, explains the company does not only adopt indie principles with its products, but in the very core of how the organization runs. In his book, The Open Organization. Jim describes the principles of such an organization:

Leaders are chosen by the teams they are going to lead. Compensation is set by peers. Resources are allocated according to market-like mechanisms. Structure will emerge only where it creates value and disappear everywhere else. Strategy making will be a dynamic, company wide conversation. Change will start in unexpected places and get rolled up, not out.

For example, when creating the strategy for shifting towards cloud services, Red Hat’s leadership leveraged their Open Decision Framework in order to solicit input from a wide array of teams, including customer support, engineering, and marketing as opposed to enforcing a policy from the top down. Jim discusses how even incredibly traditional institutions such as Procter & Gamble, Starbucks, General Electric, and IBM have benefitted from getting communities both in the company and outside of it involved in the decision making process through crowd-funding ideas, building programs to work with communities of start-ups, or having self-organizing teams run power plants.

Setting a New Standard for Ourselves and The World

Hilary Cohen knew she wanted to change the world. Yet she wrestled with a question that haunted many around her: How should the world be changed? Drawn to slogans such as Change the world. Improve lives. Invent something new., Hilary joined a prestigious consulting firm after graduating from college. However, she soon came to be bothered by the overwork and by the reality that most of the projects were corporate humdrum, not world-saving. And if the work was duller than the recruiters had promised, her fellow consultants’ workaholism was out of step with that dullness. They worked as though they were solving the urgent problems they had been pitched on fixing but weren’t.

Patricia’s story started in a way similar to Hilary’s. She also went to a prestigious university and then worked in several prestigious roles including Strategy Consultant, Product Manager, and Data Scientist. However, after all these roles, Patricia decided she wanted to work on a problem she really cared about: building a sense of community. Despite being surrounded by tech start-ups all taking a traditional approach to growth, Patricia and her co-founder Adi decided to take an indie approach: In order to optimize for intimacy over growth, we don’t intend to take VC money. We are not an accelerator, community fund, or exclusive club. Rather, we are a collective of humans with shared values of intellectual and emotional nourishment (The Commons).

Since they took an indie approach, Patricia and Adi could decide to grow The Commons at an intentional pace. While it may not have the growth metrics a VC would look for, The SF Commons was growing fine by the standards of the needs of the creators and community (I would guess, don’t want to speak for Patricia or Adi here). More importantly, to many in the community, including me, it has come to represent a really special place I look forward to going back to when in SF.

A lot of ideas do not lend themselves to the indie approach: especially ideas that require a lot of upfront capital for specialized talent, research, hardware, etc. This post is not about how the indie approach is the best approach, but simply that it is an approach that may be more broadly applicable than first meets the eye. It’s an approach that I was completely unaware of until relatively recently. So often I’ve seen friends lose motivation at their work because they can never catch enough of a break to actually do their best work, they don’t feel they have any ownership over their work, or they don’t feel they are actually helping people. I believe that the indie approach can help fix our fundamentally broken relationship with work.

But, as we explored, the indie approach can be transformational in a far deeper way. It can allow us to build in a way with a genuine intention to give and grow as opposed to wait and extract. It allows us to leverage the societal good that comes from The Network Effect, without lock-in. It empowers us to leverage our ownership through large scale collective bargaining so ground-breaking new technologies like AI can be a rising tide that lifts all boats as opposed to a powerful tool for further consolidation.

While as a kid, I dreamed of the external validation a certain path would one day give me, pursuing the indie path has made me grateful for every day I get to pursue it. While both paths are valid in their own ways depending on what you want to do, I hope that this post has opened up your mind to this new way of thinking, and that it is just as transformative for you as it has been for me.